The text below comes from my PhD thesis

General information

Vanilla planifolia is indigenous to Central America. In Mexico, vanilla fruit was called “tlilxochitl” which comes from the words “tlilli” and “xochitl” and means “black” and “pod”, respectively (Bouriquet, 1954; Purseglove et al., 1981). When the Spaniards discovered America, they called it “vanilla” that comes from the Spanish word “vaina” meaning “pod”. The latin word “planifolia” described the flatness (“plani”) of the leaves (“folia”).

Vanilla planifolia is indigenous to Central America. In Mexico, vanilla fruit was called “tlilxochitl” which comes from the words “tlilli” and “xochitl” and means “black” and “pod”, respectively (Bouriquet, 1954; Purseglove et al., 1981). When the Spaniards discovered America, they called it “vanilla” that comes from the Spanish word “vaina” meaning “pod”. The latin word “planifolia” described the flatness (“plani”) of the leaves (“folia”).

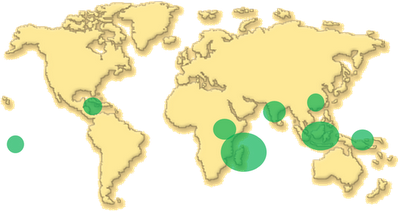

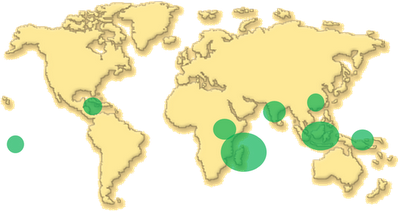

The genus Vanilla belongs to the largest family of the flowering plants, the Orchidaceae. Among the 800 genera and the 25,000 species within the family, the genus Vanilla contains by itself more than 100 species (Bory et al., 2008b). Vanilla plants are epiphytic, hemi-epiphytic or terrestrial orchids that are distributed between latitude 27° north and 27° south on all continents except Australia (Bouriquet, 1954; Soto Arenas, 2003). Aerial roots help the plants to climb on trees or various supports but also contribute to absorb water from the air humidity. Ideal soil for vanilla is light, rich in humus and porous allowing the roots to spread without excessive moisture (Bouriquet, 1954). Crops are established from vanilla vine cuttings. Vanilla plants grow better at temperature between 20 and 30°C with around 2,000 mm of rainfall per year (Bouriquet, 1954). Higher temperatures or insufficient shading are fatal to the plant. Nevertheless, excessive humidity and shading can induce susceptibility of the plant to diseases (mildew and root rot) (Bouriquet, 1954). A water stress of about 50 days is necessary to induce flowering. Flowering time of vanilla varies with the region of the world (Fouché and Jouve, 1999).

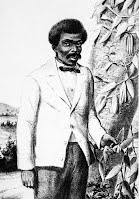

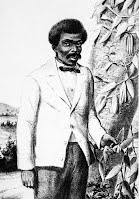

The first flowers generally appear three years or more inflorescencesafter planting. Each vanilla plant can bear 10-12 if plants are vigorous enough. But for each inflorescence, only few flowers open in a day and close up at midday. With absence of natural pollinators in the introduction areas, fruit production was impossible until Charles Morren developed an artificial method of pollination in 1836 but especially until the discovery of a practical method of vanilla hand pollination in 1841 by Edmond Albius (Rao and Ravishankar, 2000; Arditti et al., 2009).

The first flowers generally appear three years or more inflorescencesafter planting. Each vanilla plant can bear 10-12 if plants are vigorous enough. But for each inflorescence, only few flowers open in a day and close up at midday. With absence of natural pollinators in the introduction areas, fruit production was impossible until Charles Morren developed an artificial method of pollination in 1836 but especially until the discovery of a practical method of vanilla hand pollination in 1841 by Edmond Albius (Rao and Ravishankar, 2000; Arditti et al., 2009).

After fecundation, ovary develops into a fruit (usually called pod or bean). Five to six weeks later, fruit reaches full-size development. To ensure good fruit size, a maximum of ten fruits should be kept on the same inflorescence. Generally, fruits are mature eight to nine months after pollination when their colours turn from green to yellow. Although 15 vanilla species bear aromatic fruits, Vanilla planifolia is the most widely grown species for the aromatic qualities of its fruit. Despite of a smaller scale, two other species V. tahitensis J.W. Moore and V. pompona Schiede are cultivated. The former is cultivated in Tahiti and gives pods of distinctly different flavour compared to V. planifolia while the latter is more resistant against diseases but gives pods of an inferior aromatic quality.

After fecundation, ovary develops into a fruit (usually called pod or bean). Five to six weeks later, fruit reaches full-size development. To ensure good fruit size, a maximum of ten fruits should be kept on the same inflorescence. Generally, fruits are mature eight to nine months after pollination when their colours turn from green to yellow. Although 15 vanilla species bear aromatic fruits, Vanilla planifolia is the most widely grown species for the aromatic qualities of its fruit. Despite of a smaller scale, two other species V. tahitensis J.W. Moore and V. pompona Schiede are cultivated. The former is cultivated in Tahiti and gives pods of distinctly different flavour compared to V. planifolia while the latter is more resistant against diseases but gives pods of an inferior aromatic quality.

Mature green pods of V. planifolia are odourless and develop their aroma and flavour after a “curing” process. Number of procedures have been developed for curing vanilla, but they are all characterized by four phases in order to obtain a commercially viable product (Balls and Arana, 1941; Odoux, 2000; Dignum et al., 2002; Havkin-Frenkel et al., 2004; Pérez-Silva, 2006). These four phases are called “killing”, “sweating”, “drying” and “conditioning”. Vanilla planifolia fruits are dehiscent capsules that normally open at maturity. In order to keep the pods closed and thus maintain the aroma compound inside, a “killing” step is necessary to stop the vegetative development. At the same time, killing methods allow cell structure disruption and thus various enzymes can come into contact with their substrates. Killing process can be carried out by hot water scalding, sun/oven heating, scarification or freezing. The commonly used methods are sun, oven and hot water killing (Havkin-Frenkel and Dorn, 1997). The “sweating” step allows the moisture to escape rapidly in order to reach a level that will avoid microbial spoilage during the subsequent operations. This step is also crucial because it let indigenous enzymes taking effect to develop the characteristic vanilla aroma and flavour. During the “drying” step, decrease of the moisture content reduces undesirable enzyme activities and biochemical changes. Then, for the “conditioning” step, vanilla pods are stored in closed boxes for several months to refine their flavour and develop new compounds from Maillard reactions for instance. The full curing process last at least six months but can go for one year or more.

Mature green pods of V. planifolia are odourless and develop their aroma and flavour after a “curing” process. Number of procedures have been developed for curing vanilla, but they are all characterized by four phases in order to obtain a commercially viable product (Balls and Arana, 1941; Odoux, 2000; Dignum et al., 2002; Havkin-Frenkel et al., 2004; Pérez-Silva, 2006). These four phases are called “killing”, “sweating”, “drying” and “conditioning”. Vanilla planifolia fruits are dehiscent capsules that normally open at maturity. In order to keep the pods closed and thus maintain the aroma compound inside, a “killing” step is necessary to stop the vegetative development. At the same time, killing methods allow cell structure disruption and thus various enzymes can come into contact with their substrates. Killing process can be carried out by hot water scalding, sun/oven heating, scarification or freezing. The commonly used methods are sun, oven and hot water killing (Havkin-Frenkel and Dorn, 1997). The “sweating” step allows the moisture to escape rapidly in order to reach a level that will avoid microbial spoilage during the subsequent operations. This step is also crucial because it let indigenous enzymes taking effect to develop the characteristic vanilla aroma and flavour. During the “drying” step, decrease of the moisture content reduces undesirable enzyme activities and biochemical changes. Then, for the “conditioning” step, vanilla pods are stored in closed boxes for several months to refine their flavour and develop new compounds from Maillard reactions for instance. The full curing process last at least six months but can go for one year or more.

Phytochemistry

Vanillin, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde, is the major flavour compound of vanilla cured pods and was isolated for the first time by Gobley (1858). Vanillin is derived from its glucoside (glucovanillin) which is hydrolyzed during the curing process. Since other diverse reactions (oxidation, hydroxylation etc.) are taking place during the curing process, this section will focus on the phytochemistry of vanilla plant and pod prior to curing. Most of previous studies have focused on the glycosidic content of the green pods as they are supposed to be precursors of flavour compounds present in the cured pods.

The β-D-glucopyranoside of vanillin was first synthesised by Tiemann (1885) but there was no clue of its presence in vanilla green pods. Goris (1924) isolated three glucosides from green pods including glucovanillin and postulated the presence of vanillylalcohol glucoside. Later, this author reported the presence of at least four glucosides which upon hydrolysis produce vanilla aroma and flavour (Goris, 1947). Prat and Subitte (1969) reported a considerable amount of p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol in extracts of green pods. These authors have suggested that this compound may be an important intermediate in aroma development.

Tokoro et al. as well as Kanisawa et al. isolated the most abundant glucosides from green pods and identified them as glucovanillin, p-hydroxybenzylalcohol glucoside, bis[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-benzyl]-2-isopropyltartrate (glucoside A) and bis[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-benzyl]-2-(2-butyl)-tartrate (glucoside B) (Tokoro et al., 1990; Kanisawa, 1993; Kanisawa et al., 1994). These glucosides A and B were reported for the first time in vanilla and have a structure very similar to the loroglossins found in other Orchidaceae plants (Huang et al., 2004; Cota et al., 2008). Various other minor glucosides were identified after enzymatic hydrolysis: glucosides of vanillic acid, vanillyl alcohol, p-vinyl-guaiacol, acetovanillon, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, methyl-3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid, 2-methoxy-4-cresol, homovanillyl alcohol, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, ethyl-4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenylacetate, p-cresol, p-vinylphenol, methylsalicylate, p-hydroxybenzylethyl ether, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, p-hydroxycinnamic acid, cinnamic alcohol, cinnamic acid, phenethyl alcohol, 3-phenylpropanol (Kanisawa et al., 1994). Negishi and Ozawa (1996) synthesized 12 different glucosides but were able to identify only glucovanillin and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde from green pod extracts using HPLC analysis. The other glucosides were probably not formed yet in the six-months-old pods studied experimentally. Leong et al. (1989b) identified the glucosides of vanillin, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, vanillic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid in green pod extract by HPLC.

Arana (1943) postulated that most of the glucovanillin (~70%) is located in the photosynthetic mesocarp of the green mature pods. Glucovanillin has been localized anatomically in the inner region of green mature pods (Joel et al., 2003; Odoux et al., 2003b). Odoux et al. (2003b) demonstrated the accumulation of glucovanillin in the placentae, whereas Joel et al. (2003) affirmed that glucovanillin is synthesized mostly in the trichomes. In a recent study, Odoux and Brillouet (2009) unambiguously proved that glucovanillin is stored in the placental laminae (92%) of mature green pods, whereas only a small amount of glucovanillin (7%) is present in the trichomes.

Several hydrocarbons, p-demethylsterols, triterpene alcohols and long-chain aliphatic β-diketones were detected in vanilla green pods (Ramaroson-Raonizafinimanana et al., 1997, 1998, 2000). Long-chain γ-pyranones were also isolated from crushed vanilla pods and were said to come from the epicuticular wax (Ramaroson-Raonizafinimanana et al., 1999). After dissection of vanilla pods, Odoux and Brilouet (2009) argued that these long-chain γ-pyranones were more likely found in trichomes. Odoux and Brillouet (2009) also demonstrated that trichomes produce a mucilage which is made from a mixture of a glucomannan and a pectic polysaccharide.

In other parts of the plant, only few studies have been conducted. Despite of a smaller amount than in green pods, Tokoro et al. (1990) reported the presence of glucosides A and B in leaves and stems of V. planifolia. Sun et al. (2001) reported the presence of p-ethoxymethylphenol, p-butoxymethylphenol, vanillin, p-hydroxy-2-methoxycinnamaldehyde and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in the ethanol extract of vanilla leaves and stems. The authors observed that among the detected compounds, p-ethoxymethylphenol was the most abundant one. Interestingly, p-butoxymethylphenol showed a strong toxicity to mosquito larvae (Sun et al., 2001).

According to us, no studies have been reported on the organic acid content of vanilla green pods. However, Fitelson and Bowden (1968) identified malic acid as a major organic acid of vanilla extract and the presence of citric acid, isocitric acid and succinic acid was suspected. Additionnally, Martin et al. (1977) used the total and free amino acid contents to determine the authenticity of vanilla extract.

Biosynthesis of vanillin

Vanillin is obtained naturally from vanilla cured pods but can also come from other sources: (bio)conversion of related compounds or via chemical synthesis.

Zenk (1965) performed feeding experiments of vanilla green pod disks with radioactively-labelled ferulic and vanillic acids. From the results obtained, this author proposed that vanillic acid and vanillin arise from a common precursor, ferulic acid. A CoA-dependent β-oxidative cleavage of feruloyl-CoA was suggested, leading to the formation of vanilloyl-CoA. This compound could then be reduced to vanillin or deacylated to vanillic acid (Figure 7).

Kanisawa et al. (1994) measured levels of phenolic compounds during vanilla pods development. They observed a decline of glucosides A and B prior to a rise of glucovanillin. A possible “shunt” in the vanillin biosynthetic pathway involving these two tartrate bis-esters of p-hydroxybenzylalcohol β-D-glucoside was suggested and authors proposed another pathway (Figure 8).

A more complex route was later proposed by Funk and Brodelius (1990b, a, 1992) based on results from feeding experiments of radio-labelled compounds to Vanilla cell cultures. In this pathway caffeic acid, originating from phenylalanine, was methylated at the para position to produce iso-ferulic acid which was also methylated to obtain 3,4-dimethoxycinnamic acid (Figure 9). Glycosylation of this compound can occur and form glucose ester. A side-chain shortening was then proposed, forming 3,4-dimethoxybenzoic acid which after demethylation could give vanillic acid and its β-D-glucoside. Funk and Brodelius (1990b, a, 1992) postulated that the chain shortening of the phenylpropanoids takes place at the level of caffeic acid and suggested that vanillin could result from the reduction of vanillin acid.

Others studies using callus or tissue cultures showed an increase of vanillin production after ferulic acid feeding suggesting that this compound might indeed be a precursor of vanillin (Romagnoli and Knorr, 1988; Labuda et al., 1993). Nevertheless, results from cell cultures showed only conversion of non-glycosylated compounds and furthermore, Vanilla cell cultures do not normally produce vanillin in significant amounts (Figure 10). Thus, one has to consider with caution the results obtained from cell culture. Then, different biosynthetic pathways in pods and cell cultures may be possible.

Recently, Negishi et al. (2009) performed feeding experiments of 14C-labeled compounds to disk sections of V. planifolia green pods. [U-14C]-labeled p-coumaric acid, [U-14C]-labeled p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, [U-14C]-labeled p-hydroxybenzyl alcohol, [O-methyl-14C]-labeled ferulic acid were used as precursor compounds and labelled products were fractionated and identified by HPLC. From the results, the authors proposed a new biosynthetic pathway of vanillin in green pods (Figure 11).

All reported studies agree on the involvement of shikimate and phenylalanine pathways. However, there are contradictions between results obtained from green pods and cell cultures. Main question concerns the C3 side chain shortening and more precisely whether it could happen before or after hydroxylation and methylation of the aromatic ring to yield vanillin (Figure 12 and 7) and also whether glucosides or aglycones are preferentially implied in the pathway.

Biochemistry

Only few enzymes of vanillin biosynthesis pathway are known. Extensive studies were performed mostly on glucosidases involved in vanillin convertion from its glucoside, the glucovanillin.

Involvement of glucosidases in the formation of vanilla aroma was first suggested by Miller in 1754 (quoted by Janot, 1954). The presence of an enzyme converting glucovanillin to vanillin was demonstrated (Lecomte, 1901) and considered to be of a β-type (Arana, 1943). Odoux et al. (2003a) purified and characterized a vanilla β-D-glucosidase responsible for the release of aromatic vanillin from glucovanillin. The enzyme has a molecular mass of 201 kDa and is constituted of four 50 kDa subunits. Arana (1943) stated that the enzyme responsible for glucovanillin hydrolysis is present in the photosynthetic mesocarp of green mature pods and absent from the central segment. In contradiction with previous data by Arana (1943), glucosidase seems to be located preferentially in the inner part of vanilla pods (placentae and trichomes) where vanillin glucoside is also found (Odoux et al., 2003b; Odoux et al., 2006; Odoux and Brillouet, 2009). Moreover, the enzyme seems to be localized in the cytoplasm. After destruction of cell integrity during curing process, enzyme might come in contact with its substrate, the glucovanillin, in order to convert it into vanillin (Odoux et al., 2006). Content and activity of β-glucosidase increase when pod matures, closely parallely to the build-up of glucovanillin (Arana, 1943; Wild-Altamirano, 1969; Ranadive et al., 1983; Kanisawa et al., 1994). Along mature green pod, maximal activity of β-glucosidase was encountered at the blossom-end. Nevertheless, it has been shown that β-glucosidase activity decreases rapidly after the first steps of curing process (Dignum et al., 2002; Pérez-Silva, 2006). Dignum et al. (2002) and Odoux (2000) showed that hydrolysis of glucovanillin continues despite the decrease of enzymatic activity. Odoux (2004) proposed that a residual and non-detectable enzymatic activity could be maintained in the pods and might explain the total hydrolysis of glucovanillin at the end of curing process. Two glucosidases were reported by Kanisawa et al. (1994): one non-specific present in leaves and green pods, whereas the other one is specific to glucovanillin and to the green pods. Dignum et al. (2002) considered that this non specific enzyme might be degraded during thermal treatment of the first curing process steps. Recently, although in small quantities, yeasts with β-glucosidase activity have been found from soil rhizosphere, stem, leaf, flower and pod surfaces but also from the inner part of pods (General et al., 2009). Contribution of these yeasts in the hydrolysis of glucovanillin has to be considered.

Ranadive et al. (1983) concluded from their results that green vanilla pod extracts contain at least six substrate specific glycosidase activities. While activities of α-glucosidase and α- and β-mannosidase were found to be very low, β-glucosidase and α- and β-galactosidase activities were easily detected in green vanilla pods.

Several other enzymes are of interest as they might be involved in the biosynthesis of vanillin. This is the case of phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) which converts phenylalanine into cinnamic acid-type compounds which are intermediates in vanillin biosynthesis. Dignum et al. (2002) demonstrated that no β-glucosidase and PAL activity were detected in pods scalded for 20 min at 80°C. A p-hydroxy-benzaldehyde synthase (HBS), a chain shortening enzyme, has been localized by immunofluorescence in vanilla pod trichomes with an antibody raised against HBS (Joel et al., 2003). The final enzymatic step of one proposed biosynthesis pathway of vanillin is believed to be a methylation of 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde by a O-methyltransferases (OMT) (Havkin-Frenkel et al., 1999). Although purification of enzymes showing OMT activity was not successful, cDNA encoding an OMT has been isolated and characterized from V. planifolia tissue cultures (Pak et al., 2004). This enzyme shows sequence similarities with caffeic acid O-methyltransferases (COMT) reported from other plants. Two other OMTs cDNA have been isolated from V. planifolia cell cultures and expressed in E. coli (Li et al., 2006). These enzymes require a 1,2,3-trihydoxybenzene moiety for significant activity. Sequence analysis shows similarity to COMT but no activity with typical COMT substrates (Li et al., 2006). Li et al. (2006) suggested that these two new vanilla OMTs might have evolved from the COMT. Two COMTs cDNA were also isolated from cell suspension cultures of V. planifolia after addition of kinetin to the culture media (Xue and Brodelius, 1998). Glycosylation appears to be efficient in V. planifolia (Yuana et al., 2002) and thus glycosyl tranferases might be involved in the formation of glucosides.

Conversion of hydroxycinnamic acids into the corresponding CoA esters is catalyzed by a p-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL). This reaction is a key point between the phenylpropanoid pathway and other pathways leading to the production of flavonoids, lignans, lignin and related phenolic compounds. Brodelius and Xue (1997) isolated with success cDNA encoding the Vanilla 4CL from cell suspension cultures. The enzyme showed high homology for the corresponding enzymes from other species. Study of expression of this enzyme could help to understand the functional role of 4CL and regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism during defence responses.

During the curing process, pods change their colour from green to brown. This darkening could be due to the action of peroxidases (POD). A peroxidase has been isolated and characterized from vanilla mature green pods (Márquez et al., 2008). POD might play also a role in decomposition of vanillin and in flavour generation during the curing process as it can be involved in dimerization of vanillin (Gatfield et al., 2006; Schwarz and Hofmann, 2009). Dignum et al. (2002) showed that POD was still active after a scalding of 20 min at 80°C. Sreedhar et al. (2009a) observed an increase of POD and catalase (CAT) activity in vanilla shoot culture under hyperhydricity conditions. Although direct implication was not clear, increase of POD activity in leaves and stems could also be correlated to the floral induction of V. planifolia plants (Fouché and Coumans, 1995). POD activity was also shown to increase in three-months-old green vanilla pods (Wild-Altamirano, 1969). From the same study, Wild-Altamirano (1969) also observed a decrease of proteolytic activity in developing vanilla green pods. Dignum et al. (2002) demonstrated that protease activity decreases after autoclaving but still remains at the end of curing process.

Two reactions are driven by polyphenol oxidase (PPO): ortho-hydroxylation of monophenols to diphenols and oxidation of 1,2-dihydroxybenzenes to o-quinones. Enzymatic browning catalyzed by PPO is generally considered detrimental to food quality but in vanilla pods, PPO is important for colour qualities and commercial properties of cured pods. Browning in vanilla pods may result from oxidation of phenolic compounds. PPO activity was measured in acetone extract of vanilla green pods and was shown to increase with age of pods (Wild-Altamirano, 1969). Debowska and Postolski (2001) investigated PPO properties from vanilla shoot primordial and revealed presence of three isozymes. Native PPO in V. planifolia pods has been extracted and found to be a monomeric form of ~34kDa (Waliszewski et al., 2009).

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc) is omnipresent in plants. In Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) plants, the enzyme is responsible of primary carboxylation of CAM cycle. Vanilla plants are known to be an obligate CAM plants. In Vanilla plants, not only leaves, but also stem and developed aerial roots are photosynthetically active. Two PEPc isoforms were described by Gehrig et al. (1998) after isolation of cDNA and sequence analysis obtained from leaves, stems and aerial roots of V. planifolia. Sequences of the two V. planifolia PEPc isoforms are similar to each other and also with other plant sequences. Gehrig et al. (1998) demonstrated that one isoform is expressed essentially in leaves and stems, whereas another one is commonly expressed in all plant organs investigated (leaves, stems, soil-grown roots and aerial roots).

Quality-determining factors of vanilla pods

Vanilla cured pods produced by Madagascar represent more than half of world production. There, vanilla pods are classified into different grades according to their colour (red or black), shape (straight, split or non split) and length. Four major classes can be distinguished: first class, called “black” or “gourmet” pods; second class, composed of non-split red pods; third class, corresponds to split red pods while cuts and very small vanilla pods belongs to the last grade. Subclasses based on pods length are also found in second and third grades. More sub-classification exist for pods which have a colour between black and red for instance. Red pods are usually used for vanilla extract production, whereas black pods are sold mainly in retail stores because of their high value. Vanilla pods from other producing areas are classified under similar grades, even if grade names may differ. Thus, commercial quality of vanilla world production is based on colour, shape and length of cured pods and also sometimes on its water content.

The French authority “Direction Générale de la Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des Fraudes” (DGCCRF) have written a decree on analytical criteria for authenticity of vanilla (DGCCRF, 2003). A reference value of 2% of total dried weight has been defined for vanillin content in cured pods. According to these authorities, higher vanillin content could be the result of synthetic vanillin adulteration. Furthermore, “ratios” of the four major compounds (vanillin, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, vanillic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid) in cured pods are also used as quality parameter but also for authenticity. Gassenmeier et al. (2008) analyzed vanilla batches from Madagascar and many of them did not match to the so-called “ratios”. Furthermore, those analytical criteria are not directly linked to the sensorial properties of vanilla pods or extracts. Thus, future methods have to consider the sensory properties of vanilla to judge its quality instead of the use of simple and restrictive analytical parameters.

Vanilla quality can also be affected by some natural factors. Jones and Vicente (1949) showed that only pods harvested with the yellow blossom end gave a good cured product: dark brown, oily and with a pleasing “vanilla” bouquet. If harvested later, pods gave higher vanillin content but were lacking the “true vanilla” character. Similar results were obtained by Sagrero-Nieves and Schwartz (1988). Altitude effect due to temperature difference may also have an effect on vanilla quality (Jones and Vicente, 1949). Effect of root rot (caused by Fusarium sp.) on vanilla quality was also evaluated by Jones and Vicente (1949). Although, cured pods from diseased plant showed slight slower vanillin content compared to healthy plants, no organoleptic differences were concluded. Different soil amendments could also contribute to increase vanilla quality. Odoux et al. (2000) showed that appropriate amendments can almost double vanillin content in cured pods compared to pods extensively cultivated traditionally in forest. Amendments may increase nutrients income to vanilla plant and thus remove any mineral deficiencies of the soil in order to optimize vanilla vines growth (Cibes et al., 1947). Optimal growing conditions could then explain the higher vanillin (or glucovanillin) production obtained by Odoux et al. (2000).

Last factor dealt with here, but not the least, is the curing process that also affects vanilla quality. Recently, several studies have been reported to find possible limiting steps of the process (Odoux, 2000; Dignum et al., 2002; Odoux et al., 2005; Pérez-Silva, 2006; Mariezcurrena et al., 2008; Márquez and Waliszewski, 2008). Improvement of curing process using microwaves (Obolensky, 1957, 1958), solar heating system (Abdullah and Mursalim, 1997; Ratobison et al., 1998) or biotic pre-treatments (Sreedhar et al., 2007; Sreedhar et al., 2009b) have been proposed.

Pest and diseases

Vanilla cultivation tends to develop into a more intensive practice. Thus, pests and diseases affecting Vanilla are more and more occuring. In last decades, vanilla growers had to face several viral diseases. Among more than 50 viruses infecting orchids, Cymbidium mosaic virus (CymMV, Potexvirus) together with Odontoglossum ringspot virus (ORSV, Tobamovirus) are reported as the most prevalent viruses having economical effect (Zettler et al., 1990). These two viruses were also detected in Vanilla (Wisler et al., 1987; Pearson et al., 1993). They are transmitted mechanically by inoculation of infected sap and contaminated cutting tools. CymMV and ORSV may also be transmitted by contaminated pollen (Hu et al., 1994). CymMV infection of vanilla is often symptomless, however leaves flecking, stem necrotic spots and decline of the vine can be observed (Leclercq-Le Quillec et al., 2001). Potential destructive impact and rapid spread of this virus made it of interest for vanilla growers.

Farreyrol et al. (2001) were the first to report infection of Vanilla by Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV, Cucumovirus). Although the authors did not observe severe symptoms, leaves of CMV-infected plants were slightly elongated. CMV has been later detected in vanilla vines growing in India (Madhubala et al., 2005). Another virus, the Vanilla mosaic virus (VanMV, Potyvirus) causes leaf distortion and mosaic of the vines (Wisler et al., 1987; Farreyrol et al., 2006). Few other viruses have also been detected in vanilla vines: the Watermelon mosaic virus (WMV, Potyvirus), Bean common mosaic virus (BCMV, Potyvirus), Bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV, Potyvirus), Cowpea aphid-borne mosaic virus (CABMV, Potyvirus), Ornithogalum mosaic virus (OrMV, Potyvirus) and Wisteria vein mosaic virus (WVMV, Potyvirus) (Pearson et al., 1990; Wang and Pearson, 1992; Wang et al., 1993; Grisoni et al., 2004; Grisoni et al., 2006).

Virus infections can cause severe flecks, stunting and deformations of vines, leaves and flowers but control of their spread is still possible. Supply of virus-free cuttings associated with prophylactic measures and good agronomic practices, has shown to enhance sanitary state of vanilla plantations in French Polynesia (Richard et al., 2009).

Nowadays, efficient techniques have been developed to detect viruses (Wang et al., 1993; Bhat et al., 2006; Grisoni et al., 2006), and virus spread can be control with good practice cultivation. On the other hand, there are no solutions yet for the telluric fungi which have catastrophic effect on vanilla production and can even wipe out entire production. Fusarium oxysporum is the major source of trouble for vanilla growers. Fusarium is nowadays a pandemic disease affecting numerous countries. This organism is responsible of the root rot disease and can cause 40 to 50% death of vanilla vines (Childers and Cibes, 1946). In the early stage of the disease, there is first a browning and death of soil-ground roots and later of the aerial roots. The plant stops its shoot growth and begins to send out numerous aerial roots to the soil (Purseglove et al., 1981). Cibes et al. (1947) suggested that lack of nutrients, over-pollination and fruit production make vanilla plant less resistant to the disease. However, some Vanilla species, V. pompona and V. phaeantha and V. barbellata have shown resistance to Fusarium (Purseglove et al., 1981).

Phytophthora jatrophae is the source of vanilla mildew with direct economical impact since it have attacked developing fruits (Bouriquet, 1954; Purseglove et al., 1981). The disease starts to one extremity of the pod and then spread to the whole. Affected parts of pods take a brown chocolate colour. Diseased pods lose their swelling and rapidly fall to the ground (Bouriquet, 1954).

Spread of Conchaspis angraeci is also a major constraint in vanilla cultivation (Kahane et al., 2008). Although these scales were not of economic importance according to Bouriquet (1954), they are now reported to reduce the efficiency of vanilla production (Richard et al., 2003).

Vanilla planifolia is indigenous to Central America. In Mexico, vanilla fruit was called “tlilxochitl” which comes from the words “tlilli” and “xochitl” and means “black” and “pod”, respectively (Bouriquet, 1954; Purseglove et al., 1981). When the Spaniards discovered America, they called it “vanilla” that comes from the Spanish word “vaina” meaning “pod”. The latin word “planifolia” described the flatness (“plani”) of the leaves (“folia”).

Vanilla planifolia is indigenous to Central America. In Mexico, vanilla fruit was called “tlilxochitl” which comes from the words “tlilli” and “xochitl” and means “black” and “pod”, respectively (Bouriquet, 1954; Purseglove et al., 1981). When the Spaniards discovered America, they called it “vanilla” that comes from the Spanish word “vaina” meaning “pod”. The latin word “planifolia” described the flatness (“plani”) of the leaves (“folia”).

The first flowers generally appear three years or more inflorescencesafter planting. Each vanilla plant can bear 10-12 if plants are vigorous enough. But for each inflorescence, only few flowers open in a day and close up at midday. With absence of natural pollinators in the introduction areas, fruit production was impossible until Charles Morren developed an artificial method of pollination in 1836 but especially until the discovery of a practical method of vanilla hand pollination in 1841 by Edmond Albius (Rao and Ravishankar, 2000; Arditti et al., 2009).

The first flowers generally appear three years or more inflorescencesafter planting. Each vanilla plant can bear 10-12 if plants are vigorous enough. But for each inflorescence, only few flowers open in a day and close up at midday. With absence of natural pollinators in the introduction areas, fruit production was impossible until Charles Morren developed an artificial method of pollination in 1836 but especially until the discovery of a practical method of vanilla hand pollination in 1841 by Edmond Albius (Rao and Ravishankar, 2000; Arditti et al., 2009). After fecundation, ovary develops into a fruit (usually called pod or bean). Five to six weeks later, fruit reaches full-size development. To ensure good fruit size, a maximum of ten fruits should be kept on the same inflorescence. Generally, fruits are mature eight to nine months after pollination when their colours turn from green to yellow. Although 15 vanilla species bear aromatic fruits, Vanilla planifolia is the most widely grown species for the aromatic qualities of its fruit. Despite of a smaller scale, two other species V. tahitensis J.W. Moore and V. pompona Schiede are cultivated. The former is cultivated in Tahiti and gives pods of distinctly different flavour compared to V. planifolia while the latter is more resistant against diseases but gives pods of an inferior aromatic quality.

After fecundation, ovary develops into a fruit (usually called pod or bean). Five to six weeks later, fruit reaches full-size development. To ensure good fruit size, a maximum of ten fruits should be kept on the same inflorescence. Generally, fruits are mature eight to nine months after pollination when their colours turn from green to yellow. Although 15 vanilla species bear aromatic fruits, Vanilla planifolia is the most widely grown species for the aromatic qualities of its fruit. Despite of a smaller scale, two other species V. tahitensis J.W. Moore and V. pompona Schiede are cultivated. The former is cultivated in Tahiti and gives pods of distinctly different flavour compared to V. planifolia while the latter is more resistant against diseases but gives pods of an inferior aromatic quality. Mature green pods of V. planifolia are odourless and develop their aroma and flavour after a “curing” process. Number of procedures have been developed for curing vanilla, but they are all characterized by four phases in order to obtain a commercially viable product (Balls and Arana, 1941; Odoux, 2000; Dignum et al., 2002; Havkin-Frenkel et al., 2004; Pérez-Silva, 2006). These four phases are called “killing”, “sweating”, “drying” and “conditioning”. Vanilla planifolia fruits are dehiscent capsules that normally open at maturity. In order to keep the pods closed and thus maintain the aroma compound inside, a “killing” step is necessary to stop the vegetative development. At the same time, killing methods allow cell structure disruption and thus various enzymes can come into contact with their substrates. Killing process can be carried out by hot water scalding, sun/oven heating, scarification or freezing. The commonly used methods are sun, oven and hot water killing (Havkin-Frenkel and Dorn, 1997). The “sweating” step allows the moisture to escape rapidly in order to reach a level that will avoid microbial spoilage during the subsequent operations. This step is also crucial because it let indigenous enzymes taking effect to develop the characteristic vanilla aroma and flavour. During the “drying” step, decrease of the moisture content reduces undesirable enzyme activities and biochemical changes. Then, for the “conditioning” step, vanilla pods are stored in closed boxes for several months to refine their flavour and develop new compounds from Maillard reactions for instance. The full curing process last at least six months but can go for one year or more.

Mature green pods of V. planifolia are odourless and develop their aroma and flavour after a “curing” process. Number of procedures have been developed for curing vanilla, but they are all characterized by four phases in order to obtain a commercially viable product (Balls and Arana, 1941; Odoux, 2000; Dignum et al., 2002; Havkin-Frenkel et al., 2004; Pérez-Silva, 2006). These four phases are called “killing”, “sweating”, “drying” and “conditioning”. Vanilla planifolia fruits are dehiscent capsules that normally open at maturity. In order to keep the pods closed and thus maintain the aroma compound inside, a “killing” step is necessary to stop the vegetative development. At the same time, killing methods allow cell structure disruption and thus various enzymes can come into contact with their substrates. Killing process can be carried out by hot water scalding, sun/oven heating, scarification or freezing. The commonly used methods are sun, oven and hot water killing (Havkin-Frenkel and Dorn, 1997). The “sweating” step allows the moisture to escape rapidly in order to reach a level that will avoid microbial spoilage during the subsequent operations. This step is also crucial because it let indigenous enzymes taking effect to develop the characteristic vanilla aroma and flavour. During the “drying” step, decrease of the moisture content reduces undesirable enzyme activities and biochemical changes. Then, for the “conditioning” step, vanilla pods are stored in closed boxes for several months to refine their flavour and develop new compounds from Maillard reactions for instance. The full curing process last at least six months but can go for one year or more.